Understanding Bloat in Cows and How to Prevent It

🐶 Pet Star

55 min read · 13, Apr 2025

Understanding Bloat in Cows and How to Prevent It

Bloat in cows is a potentially life-threatening condition that every cattle farmer, veterinarian, and livestock handler should understand. As a common digestive disorder, bloat can occur suddenly and escalate quickly, making it crucial to identify the symptoms early and implement both preventative and emergency measures. This article will explore what bloat is, its causes, types, signs, treatments, and prevention methods to help ensure the health and productivity of your herd.

What is Bloat in Cattle?

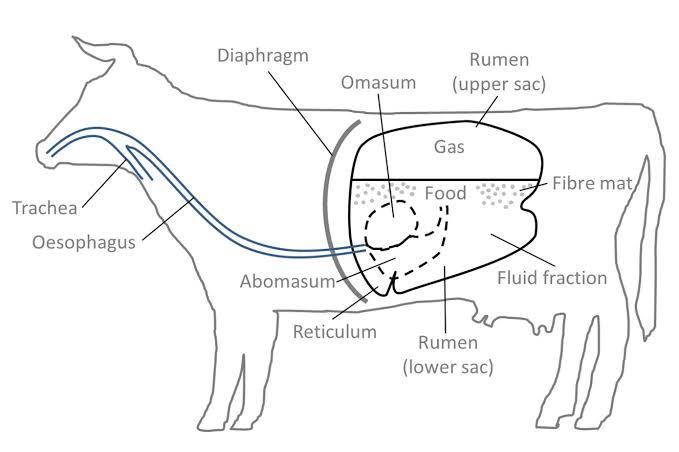

Bloat refers to the abnormal accumulation of gas in the rumen and reticulum — the first two compartments of a cow's stomach. Normally, this gas is expelled through belching (eructation), a natural process in ruminants. However, in bloat cases, gas is trapped and cannot escape, causing distention of the abdomen and pressure on internal organs, which can be fatal if not treated promptly.

Bloat interferes with respiration, circulation, and digestion. It can lead to death within hours if severe and untreated. Hence, timely diagnosis and intervention are critical.

Types of Bloat

There are two main types of bloat in cattle:

1. Frothy Bloat (Primary Ruminal Tympany)

- This type occurs when gas becomes trapped in small, stable bubbles within the rumen contents, forming a foam.

- The foam prevents normal gas escape through burping.

- It is commonly associated with diets rich in legumes (e.g., clover, alfalfa), lush green pastures, or high-grain feeds.

2. Free-Gas Bloat (Secondary Ruminal Tympany)

- Caused by physical obstruction or functional problems preventing the normal expulsion of gas.

- This type is often associated with issues like:

- Esophageal blockage

- Poor rumen motility

- Hypocalcemia

- Vagal indigestion

Causes of Bloat in Cows

The causes can be categorized based on the type of bloat:

Frothy Bloat Causes:

- Grazing on lush, immature legumes (e.g., alfalfa, clover)

- Rapid switching to high-protein, high-moisture pastures

- Consumption of finely ground grain or feedlot rations high in concentrates

- Weather changes that cause cows to gorge on pasture

Free-Gas Bloat Causes:

- Foreign bodies stuck in the esophagus

- Tumors, abscesses, or external compression of the esophagus

- Tetanus or hypocalcemia affecting muscle contractions

- Recumbency or injuries that prevent eructation

- Poor diet transition leading to rumen dysfunction

Symptoms of Bloat in Cows

Early detection is key. Watch for these clinical signs:

- Swelling on the left side of the abdomen (paralumbar fossa)

- Discomfort, restlessness, and kicking at the belly

- Excessive salivation and foaming at the mouth

- Grunting, labored breathing

- Extended neck and head

- Frequent urination and defecation attempts

- Staggering or collapse in severe cases

- Sudden death

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is typically based on visual and physical examination:

- Left-sided abdominal distension (drum-like sound on percussion)

- Ruminal fluid analysis may show foam (in frothy bloat)

- History of grazing or feeding pattern

- Passing a stomach tube can help distinguish between frothy and free-gas bloat

Treatment of Bloat

Treatment depends on the type and severity of bloat.

1. Emergency First Aid

- Insert a stomach tube to release free gas (for free-gas bloat).

- If the tube fails and the cow is in distress, a trocar or cannula can be used to puncture the rumen (emergency only).

- Call a veterinarian immediately for severe cases.

2. Treating Frothy Bloat

- Stomach tube may not relieve pressure because the foam prevents gas escape.

- Administer antifoaming agents:

- Poloxalene (commercial bloat drench)

- Mineral oil or vegetable oil

- Rumenotomy may be required in extreme cases.

3. Treating Free-Gas Bloat

- Remove physical obstructions if found.

- Correct metabolic disorders (like calcium deficiency).

- Administer drugs to stimulate rumen motility.

- Use anti-inflammatory drugs if vagus nerve damage is suspected.

Prevention of Bloat

Prevention is the most effective strategy. Key measures include:

1. Pasture Management

- Avoid sudden access to lush legumes; introduce gradually.

- Mix pastures with grasses to dilute legume content.

- Avoid grazing wet pastures (e.g., after rain or dew).

2. Feeding Practices

- Ensure proper roughage in the diet.

- Avoid finely ground or high-concentrate feed without roughage.

- Provide hay before turnout onto risky pasture.

3. Use of Anti-Bloat Products

- Supplement cattle with bloat blocks or licks containing Poloxalene.

- Drench cattle with anti-foaming agents if needed.

4. Rumen Health Monitoring

- Observe feeding behavior and rumen fill daily.

- Regularly monitor for signs of acidosis or poor digestion.

5. Strategic Grazing

- Rotate pastures frequently to control legume maturity.

- Don’t let hungry cows into high-risk pastures.

Economic Impact of Bloat

Bloat can have a considerable economic toll:

- Loss of animals due to sudden death

- Veterinary treatment costs

- Reduced weight gain or milk production

- Disruption in feeding and grazing programs

Understanding Bloat in Cows: Causes, Symptoms, and Prevention

Bloat in cows is a potentially life-threatening condition that results from an abnormal accumulation of gas in the rumen, the first chamber of the cow’s stomach. The rumen is designed to ferment food and produce gases that are typically expelled through the process of belching, or eructation. However, when gas builds up and cannot escape, it creates immense pressure on the cow's internal organs, especially the diaphragm, lungs, and heart. This pressure causes severe abdominal distension, which can compromise the animal’s ability to breathe and circulate blood. If untreated, bloat can lead to suffocation and, in extreme cases, death within just a few hours. Bloat is classified into two primary types: frothy bloat and free-gas bloat. Frothy bloat occurs when the gas produced during fermentation becomes trapped in a stable foam-like substance, making it nearly impossible for the animal to expel the gas through burping. This foam typically forms when cattle graze on certain types of forage, especially lush, high-protein legumes like alfalfa and clover, which are rich in soluble proteins that promote the creation of this foam. Lush pastures, particularly in the spring, are a major risk factor for frothy bloat, as they tend to be high in moisture and soluble nutrients that fuel the rapid fermentation of carbohydrates in the rumen. When cows are introduced to these types of pastures too quickly or in excessive amounts, the fermentation process accelerates, leading to the formation of foam and trapping gas inside the rumen. In contrast, free-gas bloat occurs when the gas fails to exit the rumen due to physical obstructions or functional impairments that prevent normal rumen motility. This can be caused by a blockage in the esophagus, injuries to the neck or throat, or metabolic disturbances such as hypocalcemia, which affects the muscle function needed for proper rumen contraction and gas expulsion. In cases of free-gas bloat, the gas produced in the rumen accumulates in the space without being trapped in foam, and it can usually be relieved by expelling the gas through a stomach tube or puncturing the rumen with a trocar to allow for its release. Although free-gas bloat is often easier to treat than frothy bloat, both conditions can rapidly escalate to dangerous levels if not managed promptly. The symptoms of bloat in cows are typically quite apparent. The most common sign is a significant swelling on the left side of the abdomen, particularly in the region of the paralumbar fossa, which is the area just behind the last rib. This swelling results from the buildup of gas in the rumen, which causes the abdomen to distend and sometimes take on a tight, drum-like appearance. Along with the physical swelling, cows affected by bloat may exhibit restlessness, often pawing at the ground, kicking at their abdomen, or attempting to lie down repeatedly. Other signs to watch for include excessive salivation, labored breathing, and foaming at the mouth, particularly in cases of frothy bloat. Cows may also appear to be in pain or discomfort, and as the condition worsens, they may become lethargic, stop eating, or show signs of collapse. If the bloat is severe, the cow may become recumbent, struggling to breathe and showing signs of circulatory shock. In some extreme cases, the pressure exerted on the diaphragm and lungs from the distended rumen can cause respiratory failure and cardiovascular collapse, leading to death. Immediate treatment is essential for bloat cases, and there are several approaches based on the type of bloat and the severity of the condition. In cases of frothy bloat, the first step is to attempt to relieve the foam in the rumen, which can be done by administering an anti-foaming agent like poloxalene, mineral oil, or vegetable oil. These agents break down the foam, allowing the gas to be expelled more easily. The best way to administer these treatments is by using a stomach tube, which not only helps deliver the anti-foaming agents directly into the rumen but can also assist in expelling any free gas that may have accumulated. For free-gas bloat, the procedure typically involves the use of a stomach tube to allow the gas to escape. If this method is not effective, rumenotomy (a surgical procedure to puncture the rumen) or the use of a trocar and cannula (a sharp, hollow needle) may be necessary to relieve the pressure. Veterinary intervention is critical, particularly in cases where a cow’s condition worsens rapidly. In addition to medical intervention, prevention is by far the best approach to avoiding the risks associated with bloat. The key to preventing bloat is proper grazing management, which includes gradual introductions to high-risk pastures, especially those containing high-protein legumes. Cattle should be acclimated slowly to these types of pastures, and access should be limited during periods of lush growth, particularly during the spring or after rain when forage moisture content is high. Adding fiber to the diet is also essential, as it promotes healthy rumen function and slows down the fermentation process, reducing the risk of bloat. Feeding strategies should also ensure that cattle have consistent access to roughage and not just high-concentrate feeds, which can lead to rapid fermentation and gas buildup. In addition to pasture management, anti-bloat supplements such as bloat blocks, licks, or oral drenching agents can help reduce the risk of frothy bloat. These products contain compounds that help break down foam and prevent gas accumulation, and they should be made available to cattle grazing on high-risk pastures. Additionally, ensuring that cattle are not under stress, are receiving adequate nutritional support, and have access to clean, fresh water can help maintain proper rumen function and prevent issues related to poor digestion. Regular health checks, especially during periods of dietary transition or after calving, can help detect early signs of ruminal dysfunction and ensure that cattle are in optimal condition. Another preventive measure is strategic grazing and pasture rotation, which can minimize the risk of overgrazing and help maintain a healthy balance of forages that are lower in protein and more resistant to fermentation-induced bloat. Managing bloat is crucial not just from an animal welfare perspective but also for its significant economic impact on livestock operations. The costs associated with treating bloat, especially when involving veterinary interventions, can be substantial, and the loss of a single animal can represent a significant financial setback, particularly in larger herds or dairy operations. Furthermore, the disruption caused by illness and treatment of bloat can result in lost productivity in terms of milk production or weight gain, further impacting profitability. Therefore, adopting a comprehensive prevention plan that focuses on diet, grazing habits, and regular health monitoring is the most effective way to minimize the risk of bloat and protect the economic viability of livestock operations. In summary, bloat in cows is a dangerous, potentially fatal condition that requires prompt recognition, intervention, and prevention. By understanding the causes, symptoms, and available treatments, farmers and livestock managers can take proactive steps to protect their cattle from bloat, ultimately improving herd health and ensuring long-term productivity. Through proper pasture management, appropriate feeding practices, and regular veterinary care, the risks associated with bloat can be significantly reduced, leading to healthier, more productive cattle.

Understanding Bloat in Cows: Causes, Symptoms, and Prevention

Bloat in cows is a potentially life-threatening condition that results from the abnormal accumulation of gas in the rumen and reticulum, the first two chambers of the cow's stomach. Under normal circumstances, these gases are expelled via belching or eructation. However, when the cow cannot release this gas, it accumulates, causing distention of the abdomen, severe discomfort, and significant pressure on internal organs such as the lungs and heart. If left untreated, bloat can lead to respiratory failure, cardiovascular collapse, and even sudden death. There are two main types of bloat in cattle: frothy bloat and free-gas bloat. Frothy bloat occurs when the gas becomes trapped in small bubbles within a foam-like substance, often due to the ingestion of lush, high-protein forages like alfalfa or clover, or a rapid change in diet that causes excessive fermentation in the rumen. The foam makes it difficult for the cow to expel the gas via burping. On the other hand, free-gas bloat happens when there is an obstruction in the esophagus or a failure of the rumen to contract properly, resulting in gas buildup that cannot escape. This can be caused by physical obstructions like foreign bodies, metabolic disturbances such as hypocalcemia, or even certain diseases that impair normal rumen function. The primary risk factors for bloat are diet-related, particularly when cattle are allowed to graze on lush pastures or are fed high-grain diets without adequate fiber. Lush grasses, especially in the spring when they are immature, tend to be high in soluble proteins, which increase the likelihood of frothy bloat. On the other hand, free-gas bloat is more commonly associated with physical issues, such as a blockage in the esophagus, or poor rumen motility, which can occur when cattle are stressed, malnourished, or suffering from certain illnesses. Recognizing the symptoms of bloat early is crucial for effective treatment. Common signs of bloat include swelling of the left side of the abdomen (which can appear as a large, bulging area), restlessness, salivation, abdominal pain, excessive burping or coughing, and a noticeable change in the cow's behavior, such as a reluctance to move or lying down more than usual. In severe cases, bloat can lead to rapid breathing, an elevated heart rate, and collapse. One of the earliest indicators of bloat is the presence of abdominal distension, which can be detected by simply observing the cow from the side. If the condition progresses, the cow may begin to show signs of severe distress, such as pacing, grunting, or even falling to the ground. In cases where gas builds up quickly, it is not uncommon for the cow to die within a few hours of the onset of symptoms due to the intense pressure on the diaphragm, heart, and lungs. The management and treatment of bloat largely depend on its type and severity. For frothy bloat, the first course of action is to administer an anti-foaming agent such as poloxalene or mineral oil, which works to break down the foam and allows gas to be expelled from the rumen. These agents can be given orally or through a stomach tube, which helps relieve pressure and restore normal digestive function. In cases of free-gas bloat, the immediate intervention is to insert a stomach tube to allow the trapped gas to escape. If this method proves ineffective, a trocar or cannula may be inserted into the rumen to create a vent for the gas. This emergency procedure is typically only performed when the cow is in extreme distress, and it is important to contact a veterinarian immediately for further treatment. If the bloat is not addressed quickly, the cow’s condition can deteriorate rapidly. The overall prognosis depends on the speed of intervention and the severity of the condition. In some cases, such as when an obstruction or significant rumen dysfunction is present, surgical intervention or more advanced treatments may be necessary. Preventing bloat is far more effective than treating it once it occurs. One of the most important prevention strategies is managing the diet and grazing behavior of cattle. When transitioning cattle onto new pastures, it is crucial to do so gradually, allowing their digestive system time to adjust to the changes in diet. Restricting access to lush legumes and high-protein forages, especially during periods of rapid pasture growth, can help reduce the risk of frothy bloat. Providing adequate roughage in the diet is also key, as it promotes proper rumen function and helps prevent the accumulation of excess gas. In addition to managing pasture quality, anti-bloat products such as bloat blocks and drenching agents are available. These products contain compounds that reduce the formation of foam in the rumen and help alleviate the risk of bloat. Regular monitoring of cattle’s grazing habits and feeding practices, including ensuring that cattle have access to clean water and avoiding abrupt dietary changes, is essential to minimizing the chances of bloat. Another critical aspect of prevention is ensuring that cattle are in optimal health. Cattle suffering from conditions like hypocalcemia, which is often associated with dairy cows after calving, are more prone to bloat due to impaired rumen motility. Similarly, cattle that are stressed or weakened by disease are more susceptible to digestive problems, including bloat. Regular health checks and maintaining cattle in a low-stress environment can go a long way in preventing not only bloat but also a range of other health issues. In the case of free-gas bloat, attention should be given to maintaining clear and open airways, ensuring that there are no obstructions in the esophagus that might prevent normal gas expulsion. This requires routine monitoring, especially after a cow has undergone medical procedures or has experienced trauma that could impact the digestive tract. Veterinary support plays a crucial role in managing bloat in cattle, as some cases may require more specialized care or diagnostic procedures to determine the underlying cause of the condition. The economic impact of bloat can be significant, especially on larger farms or commercial operations. The sudden death of cattle, veterinary costs, and potential loss of milk or weight gain can all add up. Additionally, the need for emergency medical interventions, such as surgery or extensive treatment, can further increase expenses. To minimize these costs, farmers should invest in preventive measures and ensure that their cattle are regularly monitored for signs of illness. Bloat is a serious condition that requires prompt recognition, treatment, and prevention to ensure the health and well-being of cattle. By managing grazing habits, providing a balanced diet, and maintaining overall herd health, farmers can reduce the likelihood of bloat and safeguard their livestock from this potentially deadly condition. With early intervention and careful management, bloat in cattle can be effectively controlled, allowing farmers to protect their investment and maintain a healthy, productive herd.

Summary and Conclusion

Bloat is a serious, often fatal condition in cattle, primarily caused by gas buildup in the rumen. Recognizing the types — frothy and free-gas — and understanding their causes is vital to managing your herd's health. Prevention through good pasture and feeding management, along with early intervention in cases of bloat, can drastically reduce losses.

Timely diagnosis, the use of anti-foaming agents, and veterinary support are critical. Long-term solutions lie in pasture management, gradual dietary transitions, and ensuring proper rumen function. With proper care, the risks of bloat can be minimized, promoting a healthier, more productive herd.

Q&A Section

Q1: - What is bloat in cows?

Ans: - Bloat is a condition in which gas accumulates in the rumen of a cow and cannot be expelled, causing swelling, discomfort, and potentially death if not treated.

Q2: - What are the two types of bloat?

Ans: - The two main types are frothy bloat (caused by foam in the rumen) and free-gas bloat (caused by physical obstruction or motility issues).

Q3: - How can I tell if a cow has bloat?

Ans: - Common signs include left-sided abdominal distension, labored breathing, restlessness, and foaming at the mouth.

Q4: - What is the first aid for bloat?

Ans: - In free-gas bloat, a stomach tube can help release gas. In emergencies, a trocar can be used, but always consult a vet. For frothy bloat, antifoaming agents are needed.

Q5: - How can bloat be prevented?

Ans: - Prevent bloat by managing pasture quality, avoiding sudden diet changes, using anti-bloat products, and providing adequate fiber.

Similar Articles

Find more relatable content in similar Articles

Explore Other Categories

© 2024 Copyrights by rPets. All Rights Reserved.