Vaccination Schedule for Cows: A Simple Guide

A well-structured vaccination schedule is essential for maintaining the health, productivity, and welfare of cows. Starting early in life, vaccinations prevent the spread of deadly diseases like Foot and Mouth Disease, Brucellosis, and Hemorrhagic Septicemia, ensuring herd immunity and optimal performance. This guide covers the types of vaccines, administration practices, and regional considerations for managing a healthy and disease-free herd.

🐶 Pet Star

50 min read · 13, Apr 2025

Vaccination Schedule for Cows: A Simple Guide

Vaccination plays a vital role in maintaining the health and productivity of cows, whether they're raised for dairy, beef, or breeding. By following a well-planned vaccination schedule, farmers can prevent a wide array of infectious diseases that can cause severe health problems, reduce milk yield, or even lead to the death of animals. This article provides a simple, easy-to-understand guide on the vaccination schedule for cows, including types of vaccines, timing, administration methods, and best practices.

1. Importance of Vaccination in Cows

Vaccines are biological preparations that help boost the immune system to fight specific diseases. In cows, vaccinations can:

- Prevent disease outbreaks

- Enhance productivity (milk and meat)

- Improve reproductive performance

- Reduce mortality and treatment costs

- Maintain herd health

- Ensure food safety for consumers

Diseases such as Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD), Brucellosis, Black Quarter (BQ), and Hemorrhagic Septicemia (HS) are common in cattle and can spread quickly if not controlled through vaccination.

2. Types of Vaccines for Cattle

Cattle vaccines are broadly categorized into:

- Live attenuated vaccines: Contain weakened versions of pathogens. They offer strong, long-lasting immunity but may cause mild infections.

- Inactivated (killed) vaccines: Contain killed pathogens. They are safer but may require booster doses.

- Toxoids: Used for diseases caused by toxins (e.g., Tetanus).

- Subunit/recombinant vaccines: Contain only parts of the pathogen. These are safe and specific.

3. Key Diseases and Their Vaccination Schedule

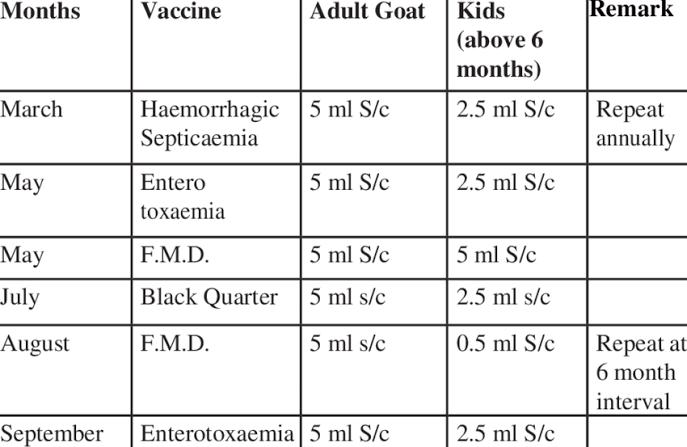

Below is a simple table summarizing the recommended vaccination schedule for common diseases in cows:

DiseaseAge at First DoseBooster DoseFrequencyNotesFoot and Mouth Disease (FMD)4–6 months1 month after 1st doseEvery 6 monthsMandatory in endemic regionsBrucellosis4–8 months (heifers only)NoneOnce in lifetimeOnly female calves vaccinatedBlack Quarter (BQ)6 months1 month after 1st doseYearlyBefore rainy seasonHemorrhagic Septicemia (HS)6 months1 month after 1st doseYearlyBefore monsoonTheileriosis4 months and aboveNoneOnce in lifetimeIn endemic areasRabiesAfter exposure or as required7, 14, 28 days post-exposureYearly if in high-risk areaFor suspected exposureAnthrax6 monthsNone or yearly depending on areaYearlyNot used in all areasTetanusBefore surgery or calving3 weeks after 1st doseAs requiredTypically given with dehorning or castrationIBR (Infectious Bovine Rhinotracheitis)3–6 months3–4 weeks laterAnnuallyFor breeding cows/bullsLeptospirosis4–6 monthsAnnuallyAnnuallyRegion-dependent

4. Vaccination Protocol by Age Group

A. Calves (Birth to 6 Months)

- At Birth: Ensure colostrum intake within 2 hours to provide passive immunity.

- 2-3 Months: Start vaccines for diseases like FMD and Theileriosis (depending on area).

- 4–6 Months: Begin BQ, HS, Brucellosis (heifers only), and others.

B. Heifers and Young Bulls (6 Months to 1 Year)

- Continue with boosters as required.

- Rabies, Anthrax, and Leptospirosis vaccines as per risk.

- De-worm before vaccination for best results.

C. Adult Cows and Bulls

- Regular boosters for FMD, HS, BQ, IBR.

- Vaccination before breeding season.

- Tetanus before calving, dehorning, or surgery.

- Annual health check-up including vaccination review.

5. Best Practices for Vaccination

- Cold Chain Maintenance: Vaccines should be stored between 2–8°C.

- De-worming: De-worm animals 10–15 days before vaccination.

- Proper Restraint: Handle animals carefully to reduce stress during vaccination.

- Use Sterile Equipment: Use clean, sterilized syringes and needles.

- Record Keeping: Maintain vaccination records with date, vaccine name, batch number.

- Observe for Reactions: Monitor cows for 1–2 hours post-vaccination for allergic reactions or fever.

6. Region-Specific Considerations

Vaccination schedules may vary depending on:

- Local climate (rainy season, temperature)

- Disease prevalence

- Animal management systems (stall-fed vs. grazing)

- Government disease control programs

For example, in India, the government often runs mass vaccination campaigns for FMD and Brucellosis. Farmers should consult local veterinarians or livestock officers to tailor the vaccination plan to their area.

7. Challenges in Vaccination

- Lack of Awareness: Many small farmers may not know the importance of vaccines.

- Poor Storage Conditions: Breaks in cold chain reduce vaccine effectiveness.

- Irregular Schedules: Missing booster doses can reduce immunity.

- Cost Constraints: Vaccination costs, though minimal, may deter very small farmers.

8. Cost and Availability of Vaccines

Vaccines for cattle are generally affordable and often subsidized by governments or NGOs. Common vaccines like FMD and HS are easily available through veterinary services, cooperatives, or private suppliers. Always check expiry dates and authenticity before buying.

Vaccination Schedule for Cows: A Comprehensive Guide

Vaccination is an essential aspect of cattle management that ensures the health, productivity, and welfare of cows, and it plays a vital role in preventing a wide variety of infectious diseases that could otherwise lead to significant losses in terms of milk production, growth, reproductive performance, and even death. The timing and administration of vaccines are critical in establishing long-term immunity and protecting herds from both common and potentially fatal diseases such as Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD), Brucellosis, Black Quarter (BQ), Hemorrhagic Septicemia (HS), Tuberculosis (TB), and Leptospirosis. For cows, a systematic vaccination schedule is a proactive health measure that involves starting the vaccination process early in life, typically when a calf is about 4 to 6 months old, depending on the vaccine and the disease being targeted. At this age, calves are no longer receiving passive immunity from their mothers' colostrum, making them susceptible to infections, so vaccinations help bolster their immune system and prevent disease outbreaks. Early vaccinations often include vaccines for diseases like FMD, BQ, and HS. FMD is one of the most highly contagious diseases that affects cattle, and it can cause severe economic losses, especially in dairy and beef production. Therefore, vaccination against FMD is essential, and in many areas, it is legally mandated. Typically, the initial dose is given at 4 to 6 months, with a booster administered 3 to 4 weeks later, and subsequent boosters every 6 months thereafter. Similarly, Black Quarter, a bacterial disease that causes sudden and severe muscle necrosis, and Hemorrhagic Septicemia, a serious bacterial infection, are often vaccinated for at 6 months of age with an annual booster before the onset of the rainy season, as these diseases are more prevalent during wet conditions. Brucellosis is another significant disease that affects cows and is typically controlled through vaccination, especially in heifer calves. The vaccine is usually administered between the ages of 4 to 8 months, and it is a one-time vaccination for life in heifers, as this disease is often sexually transmitted and can cause infertility, spontaneous abortion, and other serious reproductive issues. It is important to note that Brucellosis vaccination is only recommended for female animals, as the disease affects reproductive organs. In adult cows, especially those in high-production dairy systems or beef herds, vaccines like IBR (Infectious Bovine Rhinotracheitis), Leptospirosis, and Rabies may be included in the vaccination schedule depending on the region and the risk of exposure. IBR affects the respiratory tract and is linked to significant reproductive losses, while Leptospirosis can cause abortions, kidney damage, and milk production issues. Rabies is particularly important for cows in regions where exposure to wild animals or dogs carrying the virus is a risk. The vaccination against rabies is typically administered post-exposure if the cow is at risk of coming into contact with the virus. Adult cows may also require Tetanus vaccination, particularly before undergoing procedures like dehorning, castration, or any other surgery. This vaccination helps prevent infection from wounds that can become contaminated with Clostridium tetani bacteria, which produce a potent neurotoxin that leads to muscle rigidity and death. For pregnant cows, vaccination against diseases like Leptospirosis and IBR is often recommended before calving to ensure that their immune system is strong during delivery and that the calves receive the necessary antibodies through colostrum. Cattle farmers should also pay attention to regional disease outbreaks and environmental factors. For example, areas prone to frequent rains may have higher incidences of diseases like BQ, which thrives in wet conditions, and HS, which is often triggered by environmental stress, such as sudden changes in weather. Understanding these regional risks and consulting with veterinarians for local disease prevalence can help create a tailored vaccination schedule for each herd. An essential part of an effective vaccination strategy is maintaining a cold chain to preserve the potency of the vaccines. Vaccines should be stored in a refrigerator between 2 to 8°C and should only be used within the recommended timeframe indicated on the packaging. Using sterile equipment for administration, including clean needles and syringes, is crucial to prevent cross-contamination and infection. Additionally, deworming cattle about 10 to 15 days before vaccination is advised to ensure that the vaccines are fully effective, as worms can compromise the immune system. Keeping accurate records of vaccination schedules, including the dates, vaccine names, batch numbers, and any reactions or side effects observed, is essential not only for health monitoring but also for ensuring compliance with local and international regulations, especially in commercial farming operations. This record-keeping is vital in the case of disease outbreaks, as it helps identify the animals that may be at risk and ensures that vaccinations are up to date. Regular monitoring of the herd’s health, including a post-vaccination observation period of 24–48 hours for any adverse reactions, is also recommended to identify any possible side effects or allergic reactions. Some cows may develop mild symptoms such as swelling at the injection site, slight fever, or reduced feed intake shortly after vaccination, but these are generally short-lived and should not cause alarm. In some cases, however, more severe reactions like anaphylaxis, though rare, may occur, and it is crucial to have a veterinarian on standby to manage such emergencies. The importance of vaccination extends beyond individual animal health; it also contributes to herd health, animal welfare, and public health. In regions where diseases such as FMD and Brucellosis are prevalent, vaccination campaigns help to prevent large-scale outbreaks that can devastate local economies, disrupt food production, and result in severe trade restrictions. A vaccinated herd is less likely to transmit these diseases to other livestock or humans, which makes vaccination an essential tool in protecting both the farming community and consumers. For small-scale farmers and those in developing regions, government programs and local veterinary services often offer subsidies or free vaccination drives to help increase vaccination coverage and combat the spread of disease. Although vaccination schedules can be costly and require regular updates, the benefits far outweigh the costs in terms of reduced disease outbreaks, higher productivity, improved animal welfare, and financial gains. Effective vaccination practices also minimize the need for costly antibiotics and other veterinary treatments, which can become ineffective and contribute to the global problem of antimicrobial resistance if overused. Furthermore, as global climates change, shifting weather patterns can alter disease transmission rates, making vaccination schedules more dynamic and responsive to emerging risks. Farmers must adapt to these changes and stay informed about local disease outbreaks and vaccine availability, which can often be facilitated through regular consultations with veterinarians and agriculture extension officers. In conclusion, a comprehensive vaccination schedule is one of the most effective ways to ensure the health and productivity of cows. By vaccinating early and consistently, following region-specific guidelines, maintaining cold storage and proper administration practices, and monitoring animal health, farmers can reduce the risk of disease, enhance herd performance, and ensure a sustainable and profitable farming operation.

Vaccination Schedule for Cows: A Simple Guide

Vaccination is a fundamental aspect of cattle health management and plays a pivotal role in safeguarding the health, productivity, and longevity of cows across dairy, beef, and breeding operations. As part of proactive livestock management, implementing a timely and consistent vaccination schedule helps prevent economically devastating diseases such as Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD), Brucellosis, Black Quarter (BQ), Hemorrhagic Septicemia (HS), and others that can impair animal performance, reduce milk yield, affect reproductive capacity, and sometimes lead to death. Cows, like all mammals, are susceptible to a wide array of bacterial, viral, and protozoal infections, many of which are preventable with appropriate vaccination. The primary objective of vaccination is to stimulate the cow’s immune system to recognize and combat pathogens effectively if they are encountered in the future. This proactive approach not only benefits the individual animal but also supports herd immunity, which is critical in preventing large-scale disease outbreaks. Vaccines used in cattle generally fall into categories such as live attenuated vaccines (which use weakened pathogens), inactivated or killed vaccines, toxoids (for toxin-caused diseases like tetanus), and subunit or recombinant vaccines, which are highly specific and safe. A well-structured schedule typically begins in early calfhood, often around 4 to 6 months of age, when maternal immunity starts to wane and the calf's own immune system becomes more responsive. The first year of a cow’s life is critical, and vaccines like FMD, HS, BQ, and Brucellosis (for female calves) are administered during this phase, with boosters scheduled within 2 to 4 weeks of the initial dose to solidify immune memory. For instance, calves usually receive the FMD vaccine at 4 to 6 months old, with a booster one month later, and then every six months thereafter in high-risk areas. Black Quarter and Hemorrhagic Septicemia vaccinations are usually administered at 6 months of age and repeated annually before the onset of the rainy season, when these diseases are more prevalent. Brucellosis vaccination is typically done once in a lifetime between 4 and 8 months of age, and only female calves are vaccinated due to the reproductive nature of the disease. Similarly, Theileriosis, another major concern in certain regions, especially in crossbred cattle, may require a one-time vaccination around 4 months of age if the disease is prevalent locally. In adult cows and bulls, the vaccination focus shifts to maintenance via regular boosters and disease-specific vaccines depending on region, herd size, and management practices. For example, dairy cows in breeding programs often require vaccination against Infectious Bovine Rhinotracheitis (IBR) and Leptospirosis to protect reproductive performance. Rabies vaccination may also be necessary in regions where the virus is endemic or in cases of suspected exposure, particularly if the animal has been bitten by a wild or stray animal. Tetanus vaccines are commonly administered before calving, surgical procedures like dehorning, or during injury treatment. The timing of vaccinations can also vary depending on climate and disease outbreak patterns; for example, regions experiencing monsoon climates will often schedule HS and BQ vaccinations just before the rainy season. It's also important to understand that no vaccine is a silver bullet — the effectiveness of any vaccination program is greatly enhanced when paired with proper nutrition, hygiene, deworming (ideally 10–15 days before vaccination), and stress-free animal handling. Proper storage of vaccines is another vital element — most cattle vaccines require cold storage between 2°C and 8°C, and once opened, they must be used promptly to avoid degradation. Administration should always be done using clean, sterilized syringes and needles, and intramuscular or subcutaneous routes are commonly used based on manufacturer guidelines. It's strongly recommended that farmers maintain detailed records of all vaccinations, including the date, vaccine batch number, dose, and site of injection, for each animal in the herd. These records not only help track immunity but are also useful for demonstrating compliance with animal health standards, particularly in commercial and export-oriented operations. While the science and scheduling behind vaccinations may seem complex at first, government programs, veterinary professionals, and livestock health officers often provide free or subsidized vaccination services, especially for notifiable diseases like FMD and Brucellosis. Challenges such as low awareness, lack of access to veterinary care, or inconsistent implementation do exist, especially among smallholder and subsistence farmers, but these can be mitigated through education, farmer training programs, and public health campaigns. Ultimately, an effective vaccination schedule is a low-cost, high-return investment that improves not just individual animal health but also boosts farm productivity, consumer safety, and national food security. It reduces the need for antibiotics and other medications, thereby lowering the risk of antimicrobial resistance, which is a growing global concern. Vaccinated cows have better resistance to infections, higher fertility rates, fewer abortions, and are less likely to transmit zoonotic diseases to humans — a key consideration in today’s world where the One Health approach (integrating animal, human, and environmental health) is gaining momentum. Moreover, in the context of climate change, as shifting weather patterns expand the geographical range of certain cattle diseases, adhering to a flexible and responsive vaccination protocol becomes even more critical. Whether you are a seasoned dairy farmer, a beginner with a small backyard herd, or a commercial beef producer, understanding and implementing a simple yet scientifically informed vaccination schedule is crucial. The best approach is to work closely with a licensed veterinarian or animal health technician to design a plan that suits your herd’s specific needs, regional disease risks, and management practices. Regular health check-ups, vaccination drives, and public-private partnerships in veterinary services can make a tremendous difference. In conclusion, vaccination is not merely a protective measure; it is a proactive strategy that empowers cattle farmers to safeguard their investment, ensure animal welfare, and contribute to a safer, more sustainable food system for everyone.

Summary

Vaccination is a cornerstone of preventive veterinary medicine. By following a systematic schedule from calfhood to adulthood, farmers can protect their cows from major infectious diseases. Early-age vaccinations, boosters, and region-specific planning ensure effective disease control and promote a healthier, more productive herd.

Conclusion

A proper vaccination schedule for cows is essential not just for animal health, but also for food safety, public health, and farm profitability. Regular vaccinations reduce the need for costly treatments and losses due to disease outbreaks. With increasing awareness and veterinary support, more farmers are embracing vaccination as a routine part of cattle management. It is a small investment with large, long-term benefits.

Q&A Section

Q1:– What is the ideal age to start vaccinating a calf?

Ans:– Most vaccinations begin around 4 to 6 months of age. However, ensuring colostrum intake at birth is crucial for passive immunity.

Q2:– Is vaccination compulsory for all cows?

Ans:– While not legally compulsory everywhere, vaccines for diseases like FMD and Brucellosis are often mandated in endemic zones and highly recommended for herd health.

Q3:– Can I vaccinate a sick cow?

Ans:– No, sick or stressed cows should not be vaccinated. Wait until the cow recovers before administering vaccines.

Q4:– How often should cows be vaccinated for FMD?

Ans:– Cows should be vaccinated for FMD every 6 months in endemic regions.

Q5:– What are the side effects of cow vaccines?

Ans:– Minor side effects may include swelling at the injection site, mild fever, or temporary discomfort. Severe reactions are rare.

Similar Articles

Find more relatable content in similar Articles

Explore Other Categories

© 2024 Copyrights by rPets. All Rights Reserved.