Mycobacteriosis in lion

Mycobacteriosis, primarily caused by Mycobacterium bovis and Mycobacterium tuberculosis, poses significant risks to lion populations. This chronic disease, often undetected in early stages, affects their respiratory and systemic health. Transmission occurs through infected prey, livestock, or humans. Effective diagnosis and treatment remain challenging, while conservation efforts focus on preventing disease spread, enhancing veterinary care, and ensuring ecosystem stability, as lions are crucial

🐶 Pet Star

63 min read · 30, Mar 2025

Mycobacteriosis in Lions: A Detailed Exploration

Introduction

Mycobacteriosis is a bacterial infection caused by various species of the genus Mycobacterium, which are known to infect a wide range of animals, including humans. In wild animals, such as lions (Panthera leo), mycobacteriosis has become an emerging health concern. Lions are apex predators and serve as a keystone species in their ecosystems, and their health is indicative of the overall state of the environment in which they reside. The infection is most often caused by Mycobacterium bovis and Mycobacterium tuberculosis, but it can also be due to other mycobacteria species. This article will delve into the causes, symptoms, transmission, diagnosis, treatment, and the broader implications of mycobacteriosis in lions.

1. Understanding Mycobacteriosis in Lions

Mycobacteriosis in lions can be caused by several strains of Mycobacterium, including M. bovis and M. tuberculosis. These bacteria primarily affect the lungs, but they can also impact other organs such as the liver, spleen, and kidneys. The infection can result in severe illness and, if left untreated, may lead to death. The disease is often chronic, developing over months or even years before becoming severe enough to cause noticeable symptoms.

1.1 Mycobacterium Species in Lions

- Mycobacterium bovis: This strain is responsible for bovine tuberculosis and is often transmitted from infected cattle to wildlife, including lions. M. bovis is highly zoonotic, meaning it can be transmitted from animals to humans, raising concerns for both wildlife conservationists and the general public.

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis: Though less common, this strain of bacteria is responsible for human tuberculosis. Lions, particularly those in captivity or near human populations, can be infected by exposure to humans or other infected animals.

- Other Mycobacterium Species: Less commonly, lions can be infected by other non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM), which may also cause disease, but these infections are typically less severe.

2. Causes and Risk Factors for Mycobacteriosis in Lions

Mycobacteriosis in lions is primarily caused by exposure to infected animals or contaminated environments. Some of the main risk factors include:

2.1 Direct Transmission from Infected Wildlife or Livestock

In many cases, lions contract mycobacteriosis through direct contact with infected animals. This includes:

- Infected Cattle: In regions where lions live near human settlements or livestock farms, M. bovis can be transmitted through consumption of contaminated meat or exposure to infected carcasses.

- Other Wildlife Species: Lions in proximity to other wildlife species, such as antelope or buffalo, which may harbor the bacteria, are also at risk. The interaction between different species can facilitate the spread of the disease.

2.2 Environmental Exposure

Lions living in areas with high concentrations of infected animals, especially in captive environments like zoos or reserves, may have a higher risk of contracting mycobacteriosis. The bacteria can persist in the environment, particularly in soil or water contaminated by infected animals’ feces, urine, or respiratory droplets.

2.3 Cross-Species Transmission

Lions in proximity to humans or domestic animals, including household pets, may be at risk of contracting M. tuberculosis through contact with infected individuals. This is more common in captivity, where lions may be in close quarters with humans and domestic animals.

3. Symptoms of Mycobacteriosis in Lions

The symptoms of mycobacteriosis in lions are often insidious, developing gradually over time. Early signs may be subtle, making early detection challenging. As the disease progresses, however, more severe symptoms emerge.

3.1 Respiratory Symptoms

- Coughing: As with human tuberculosis, coughing is one of the most common symptoms of mycobacteriosis in lions, though it may be mild and intermittent at first.

- Labored Breathing: Difficulty breathing, or labored breathing, occurs as the bacteria cause inflammation in the lungs. This can be particularly problematic for apex predators like lions, who rely on efficient respiration during hunting.

- Nasal Discharge: Infected lions may exhibit a runny nose, often with thick, yellowish or greenish discharge, which may indicate a bacterial infection in the upper respiratory tract.

3.2 Generalized Symptoms

- Weight Loss: Like many chronic infections, mycobacteriosis leads to weight loss. Infected lions may lose their appetite and become lethargic, which can exacerbate their condition.

- Fever: A persistent low-grade fever is common in mycobacteriosis cases, though it may be difficult to detect without clinical intervention.

- Lethargy and Weakness: As the infection progresses, lions may exhibit general weakness and reduced physical activity. They may be less active during hunting and social behaviors, which can be detrimental to their survival in the wild.

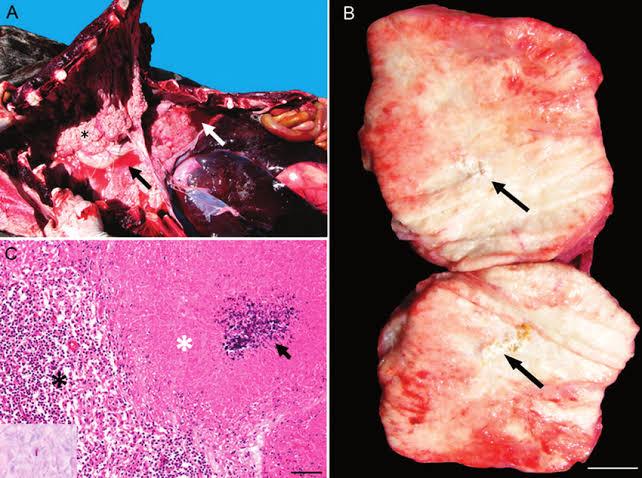

3.3 Lesions and Tumors

As the infection spreads, lesions may form in the lungs, liver, kidneys, and spleen. In severe cases, these lesions can develop into tumors or abscesses that can compromise the organ’s function.

4. Diagnosis of Mycobacteriosis in Lions

Diagnosing mycobacteriosis in lions can be challenging due to the gradual onset of symptoms and the difficulty in distinguishing the disease from other common feline illnesses. A combination of clinical signs, laboratory tests, and imaging techniques is usually required for a definitive diagnosis.

4.1 Clinical Examination

Veterinarians may start with a physical examination to identify visible symptoms such as weight loss, labored breathing, or abnormal discharge. However, these signs are not specific to mycobacteriosis and can occur in other diseases.

4.2 Laboratory Tests

- PCR Testing: Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a molecular technique used to detect the genetic material of Mycobacterium species. It can be used on respiratory samples, blood, or tissue from affected organs to confirm the presence of the bacteria.

- Culture and Sensitivity Testing: A culture test can be conducted to isolate the bacteria from infected tissue. Sensitivity testing determines which antibiotics the bacteria are sensitive to, helping guide treatment.

- Skin Tests: In some cases, similar to the tuberculin skin test used for diagnosing tuberculosis in humans and livestock, a skin test may be conducted to check for immune responses to mycobacteria. However, this test can have false negatives, particularly in wild animals.

4.3 Imaging Techniques

X-rays or ultrasounds can be used to detect lung lesions, tumors, or other abnormalities in internal organs, helping assess the severity of the infection.

5. Treatment of Mycobacteriosis in Lions

Treatment for mycobacteriosis in lions is difficult and often not successful, particularly in wild populations. Antibiotics may be used, but resistance is a significant concern, especially with M. tuberculosis and M. bovis. Moreover, long-term treatment regimens, which may last for months or even years, are difficult to administer in wild lions.

5.1 Antimicrobial Therapy

- Rifampin and Isoniazid: These are commonly used in the treatment of tuberculosis in humans, and they may be administered to infected lions. However, the dosage and duration of treatment required are still areas of active research.

- Combination Therapy: A combination of antibiotics may be necessary to treat infections caused by non-tuberculous mycobacteria. However, there is no standardized treatment protocol for lions specifically.

5.2 Surgical Intervention

In some cases, surgical removal of abscesses or tumors caused by the infection may be considered. This approach, however, is often not practical for wild lions.

5.3 Management and Quarantine

In a controlled environment such as a zoo or wildlife reserve, infected lions may be quarantined to prevent the spread of infection to other animals. Environmental sanitation and the removal of contaminated carcasses are crucial to preventing the spread of Mycobacterium species.

6. Impact on Lion Populations

Mycobacteriosis in lions can have significant ecological consequences. Lions play a vital role as apex predators in their ecosystems. A reduction in their population due to disease could have cascading effects on prey species and the overall health of the environment.

6.1 Declining Lion Populations

In regions where mycobacteriosis is prevalent, the disease may contribute to the declining lion population. Reduced reproduction rates and increased mortality due to illness could lead to population instability. This is particularly concerning for lions already threatened by habitat loss and human-wildlife conflict.

6.2 Conservation Efforts

To combat the spread of mycobacteriosis, conservationists and wildlife managers are increasing monitoring efforts. Surveillance programs that test lions for tuberculosis and other diseases are becoming more common in areas like southern Africa, where human-wildlife interactions are more frequent.

Mycobacteriosis in Lions: A Comprehensive Overview of Pathogenesis, Transmission, Diagnosis, and Conservation Implications

Mycobacteriosis in lions, caused primarily by Mycobacterium bovis and Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is an emerging infectious disease that presents significant challenges to both wild and captive lion populations. These mycobacteria are responsible for a range of diseases in mammals, most notably tuberculosis, and their impact on apex predators like lions is increasingly being recognized as a threat to both animal health and ecosystem stability. Mycobacteriosis in lions typically manifests as a chronic and progressive infection, often beginning with subtle clinical signs that make early detection difficult. Lions, as apex predators, play a crucial role in regulating prey populations and maintaining the ecological balance of their habitats, so the health of these animals is of utmost importance to the overall integrity of their environments. The transmission of mycobacteriosis occurs through direct contact with infected animals or their carcasses, or indirectly through environmental exposure to contaminated food sources or water. Lions living in areas with high densities of domestic livestock or in proximity to human settlements are at an elevated risk of contracting Mycobacterium bovis, as cattle are one of the primary hosts for the bacteria. Additionally, captive lions in zoos or wildlife reserves may also be exposed to Mycobacterium tuberculosis from human caretakers or other infected animals. The disease primarily affects the respiratory system, leading to symptoms such as coughing, labored breathing, nasal discharge, and a general decline in health, including significant weight loss and lethargy. In advanced cases, the infection can spread to other organs, such as the liver, spleen, and kidneys, resulting in the formation of granulomas or abscesses. However, the insidious nature of mycobacteriosis means that lions may carry the infection for months or even years without showing overt symptoms, complicating efforts for early diagnosis. The slow progression of the disease is coupled with the difficulty of obtaining accurate diagnoses in wild lion populations. Veterinary interventions often rely on a combination of clinical observations, laboratory tests such as PCR (polymerase chain reaction) to detect bacterial DNA, cultures for bacterial isolation, and imaging techniques to identify lesions in the lungs and other organs. However, despite these diagnostic tools, the ability to detect mycobacteriosis in free-ranging lions remains limited, especially in remote areas with inadequate veterinary infrastructure. The complexity of diagnosing and managing mycobacteriosis in lions is compounded by the challenges of treatment. Unlike human patients, who can be administered consistent and prolonged courses of antibiotics, treating wild lions with effective drug regimens is far more difficult due to logistical constraints and the aggressive nature of the disease. Drugs such as rifampin and isoniazid, which are used in the treatment of human tuberculosis, have been explored in veterinary settings, but the optimal dosages and duration of therapy remain unclear. Furthermore, long-term treatment, which may extend for months or even years, is not feasible in wild populations, where capturing and medicating lions is impractical and risky. In captivity, some success has been achieved by isolating infected individuals and administering the appropriate antibiotics under controlled conditions, but even this approach faces significant challenges, particularly in larger zoos and wildlife parks where space constraints and limited resources can hinder comprehensive disease management. The prevalence of mycobacteriosis in lions is also influenced by the broader environmental and ecological factors in which they live. In areas with high human-wildlife conflict, lions are at increased risk of coming into contact with domestic livestock, which are frequently infected with Mycobacterium bovis. This zoonotic pathogen is capable of crossing the species barrier, infecting not only lions but also humans, creating a public health risk. In addition, in regions where conservation efforts focus on habitat restoration or reintroduction programs, the spread of disease can undermine these initiatives, especially if infected individuals are inadvertently released into the wild. In such cases, wildlife managers must balance disease control with the need to maintain genetic diversity and prevent inbreeding among lion populations. As mycobacteriosis is not an isolated threat but part of a broader context of conservation challenges, effective management strategies require a multi-disciplinary approach. Monitoring programs, including routine testing of lions and other wildlife species in areas of high risk, are crucial for detecting the presence of mycobacteriosis early. Such surveillance efforts are particularly important in regions where lions live alongside domestic animals and in tourist areas where human-animal interactions are common. Furthermore, enhanced education for local communities about the importance of preventing disease transmission from livestock to wildlife, as well as increasing awareness of the risks of tuberculosis in humans and animals, are key components of a holistic disease management strategy. Preventive measures, such as vaccinating livestock against Mycobacterium bovis, controlling the movement of infected animals, and implementing quarantine protocols for new arrivals in wildlife reserves, are essential in minimizing the spread of mycobacteriosis among lions and other wildlife species. Additionally, increasing the availability of veterinary care and improving diagnostic technologies can help facilitate quicker and more accurate identification of mycobacteriosis in lions. Conservationists also recognize that addressing the impacts of mycobacteriosis requires a nuanced understanding of its ecological consequences. Lions are not only crucial for maintaining prey populations but also play an integral role in the broader ecological web. By controlling herbivore populations, lions prevent overgrazing and help maintain the structure of plant communities. A decline in lion numbers, driven by disease, could have cascading effects throughout the ecosystem, potentially altering the balance of species and habitats. Moreover, a reduction in lion populations can exacerbate human-wildlife conflict, as lions may venture into human settlements in search of food, increasing the likelihood of negative interactions with local communities. These multifaceted consequences underscore the importance of addressing mycobacteriosis as part of a broader strategy to ensure the health and sustainability of lion populations. In conclusion, while mycobacteriosis in lions presents significant challenges to wildlife health, conservation efforts aimed at early detection, improved veterinary care, and collaborative management strategies between wildlife conservationists, veterinarians, and local communities can help mitigate the impact of the disease. By addressing the underlying environmental and ecological factors that contribute to the spread of mycobacteriosis, it is possible to protect not only lions but also the broader biodiversity that depends on their existence. Given that lions play a central role in the ecological balance of their habitats, the continued health of these majestic animals is critical to the overall stability of their ecosystems, making the control and management of mycobacteriosis an essential component of lion conservation strategies worldwide.

Mycobacteriosis in Lions: An In-Depth Overview

Mycobacteriosis in lions is an emerging concern for wildlife health and conservation, primarily caused by Mycobacterium bovis and Mycobacterium tuberculosis, two highly infectious strains of bacteria. These mycobacteria are capable of infecting various animal species, including lions, and are most notorious for causing tuberculosis in both humans and livestock. In lions, the disease presents a complex challenge due to its often insidious nature, making it difficult to detect in the early stages. Mycobacteriosis in lions, much like in other wildlife species, typically begins with subtle signs that may go unnoticed for extended periods, which complicates diagnosis and effective treatment. Lions in the wild are particularly vulnerable to this infection as they are exposed to various sources of the bacteria, such as infected prey, carcasses, or livestock in proximity to their territories. The spread of Mycobacterium species is exacerbated by the increased interaction between wildlife and human populations in regions where lions roam, such as in Africa and parts of Asia. This zoonotic risk—meaning the bacteria can be transmitted from animals to humans—raises significant concerns for both wildlife conservationists and public health authorities, especially in areas where human-wildlife conflict is prevalent. One of the primary factors driving the spread of mycobacteriosis among lions is their scavenging behavior, which places them at higher risk of ingesting or coming into direct contact with infected animal carcasses, including livestock. In some instances, lions living in or near protected reserves or zoos may also contract the disease from domestic animals or caretakers, particularly if tuberculosis is present in the human population. As the disease progresses, lions may exhibit a range of symptoms such as coughing, nasal discharge, weight loss, lethargy, and respiratory distress, which are similar to those observed in other species suffering from tuberculosis. The infection typically starts in the lungs but can spread to other organs, including the liver, spleen, and kidneys, leading to systemic involvement and the formation of abscesses or granulomas. One of the most concerning aspects of mycobacteriosis is its chronic nature. Lions may carry the bacteria for extended periods without showing outward signs of illness, leading to silent transmission and undetected outbreaks in lion populations. Diagnosis, therefore, requires a combination of laboratory tests such as PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) for genetic material, culture techniques for isolating the bacteria, and imaging studies to assess internal organ involvement. In addition, veterinarians often employ skin tests to check for immune responses similar to those used in tuberculosis testing for livestock, although these tests may sometimes yield false-negative results in wild populations. However, the challenge of diagnosing mycobacteriosis in lions goes beyond technical limitations; it is also a matter of logistics. In many remote areas where lions live, veterinary services may not be readily accessible, making it difficult to conduct comprehensive health assessments or monitor disease progression. Furthermore, the treatment of mycobacteriosis in lions remains a significant obstacle due to the difficulty of administering long-term antibiotic therapies in wild populations. While drugs like rifampin and isoniazid have been used to treat tuberculosis in humans, their use in lions is less well-documented, and the appropriate dosages and treatment durations are still areas of active research. In captivity, where lions are more likely to receive treatment, the challenge lies in the practicality of adhering to strict medication regimens over an extended period, which can be complicated by the lions' natural behavior and resistance to being medicated. The consequences of untreated mycobacteriosis in lions can be dire, not only for the individual animals affected but also for entire lion populations. Lions are apex predators, meaning they play a vital role in maintaining the balance of their ecosystems by regulating the populations of herbivores and smaller carnivores. A decline in lion numbers due to mycobacteriosis can lead to ecological imbalance, which may cause an overpopulation of certain prey species and subsequent damage to vegetation and ecosystems. Moreover, a reduction in the lion population can have cascading effects on other species, including scavengers and smaller carnivores that rely on lion kills for food. In the wild, the spread of mycobacteriosis can be particularly devastating for already endangered lion populations. In regions where lions are already facing significant threats, such as habitat loss, human-wildlife conflict, and poaching, the addition of a disease like mycobacteriosis can push populations to the brink of extinction. In response, conservation efforts are increasingly focusing on disease surveillance and monitoring, recognizing that the health of lion populations is integral to the broader biodiversity of their habitats. Conservationists are working to establish testing and monitoring programs in areas with high lion populations, and they are also focusing on educating local communities about the risks of disease transmission and the importance of wildlife health. In some cases, these efforts are coupled with initiatives aimed at reducing human-wildlife conflict and promoting coexistence between local communities and wildlife. Additionally, some reserves have implemented quarantine protocols to isolate sick lions and prevent the spread of mycobacteriosis to other animals, while veterinarians work on developing more effective treatment strategies. Preventive measures, such as the vaccination of livestock against M. bovis and controlling the movement of potentially infected animals, have been suggested as part of broader disease management strategies in regions where lions come into contact with domestic animals. Despite the challenges, addressing mycobacteriosis in lions requires a multi-faceted approach that combines veterinary science, conservation efforts, and community engagement. The survival of lions as a species—and their role in maintaining ecosystem health—depends on a concerted effort to mitigate the effects of this disease, as well as on increasing the understanding of how it spreads and impacts these majestic animals. While mycobacteriosis poses a significant threat to lion populations, addressing it with proactive and scientifically informed approaches can help secure a future for lions and ensure the health of their ecosystems.

Summary

Mycobacteriosis in lions is a serious concern for wildlife health and conservation. The disease is primarily caused by Mycobacterium bovis and Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and it can lead to significant health problems in affected lions. The primary symptoms include coughing, weight loss, fever, and respiratory issues, which may be hard to detect in the early stages. Diagnosis is typically done through PCR testing, culture methods, and imaging techniques. Treatment remains challenging due to antibiotic resistance and the difficulty of administering long-term therapy to wild animals. The disease has significant ecological implications, as it can reduce lion populations, which in turn affects the broader ecosystem. Conservation efforts to monitor and manage mycobacteriosis are essential for the health and survival of lion populations in the wild.

Conclusions

Mycobacteriosis represents a growing threat to lion populations, particularly in areas where they come into contact with domestic livestock or other wildlife. Early detection, adequate treatment, and preventive measures such as vaccination programs and environmental sanitation are crucial to limiting the spread of the disease. Additionally, further research into effective treatment regimens for wild animals is needed. Conservation efforts must continue to focus on monitoring and protecting lions to ensure their continued survival and to safeguard the delicate balance of their ecosystems.

Q&A Section

Q1: What is mycobacteriosis in lions?

Ans: Mycobacteriosis in lions is a bacterial infection caused by species of the Mycobacterium genus, such as Mycobacterium bovis and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It can cause respiratory issues, weight loss, and other systemic symptoms, and it poses a significant threat to both wild and captive lion populations.

Q2: How is mycobacteriosis transmitted to lions?

Ans: Mycobacteriosis can be transmitted to lions through direct contact with infected animals, consumption of contaminated meat, or exposure to contaminated environments. It can also spread through cross-species transmission, particularly from livestock or humans.

Q3: What are the main symptoms of mycobacteriosis in lions?

Ans: The primary symptoms include coughing, labored breathing, nasal discharge, weight loss, fever, and lethargy. In severe cases, lesions and abscesses may develop in internal organs such as the lungs, liver, and kidneys.

Q4: How is mycobacteriosis diagnosed in lions?

Ans: Diagnosis typically involves a combination of clinical examination, PCR testing, culture methods, imaging techniques, and sometimes skin tests. The tests help confirm the presence of Mycobacterium species in tissues or bodily fluids.

Q5: Can mycobacteriosis in lions be treated?

Ans: Treatment is difficult due to antibiotic resistance, and there are no standardized treatment protocols for wild lions. Antimicrobial therapy, such as the use of rifampin and isoniazid, may be effective, but long-term administration is challenging in wild settings.

Similar Articles

Find more relatable content in similar Articles

Explore Other Categories

© 2024 Copyrights by rPets. All Rights Reserved.