Feline Leukemia Virus (FeLV) in lion

Feline Leukemia Virus (FeLV) is a severe viral infection that affects both domestic and wild cats, including lions. The virus weakens the immune system, leading to anemia, cancer, and other health issues, with potentially fatal consequences. This overview explores FeLV's transmission, diagnosis, impact on lion populations, conservation efforts, and the challenges involved in managing the disease, offering insights into the ongoing battle to protect these majestic creatures.

🐶 Pet Star

63 min read · 29, Mar 2025

Feline Leukemia Virus (FeLV) in Lions

Introduction to Feline Leukemia Virus (FeLV)

Feline Leukemia Virus (FeLV) is one of the most significant viral infections that can affect domestic cats, and its presence in wild feline populations, including lions (Panthera leo), is of considerable concern to wildlife veterinarians, conservationists, and zoologists. FeLV is a retrovirus that targets the immune system and leads to a variety of health issues, including immunosuppression, anemia, reproductive failure, and an increased susceptibility to other infections and cancers.

The virus is spread primarily through close contact, including grooming, biting, or sharing food and water dishes. Although FeLV is primarily known to affect domestic cats, its impact on wild cats, particularly lions in both captivity and the wild, has garnered significant attention. Infected animals may develop symptoms ranging from mild to severe, and in many cases, FeLV can lead to premature death due to secondary infections, cancer, or organ failure.

This article explores the nature of FeLV in lions, how it affects these majestic predators, the transmission pathways, diagnostic methods, treatment options, and ongoing conservation efforts to protect lion populations from the virus.

What is FeLV?

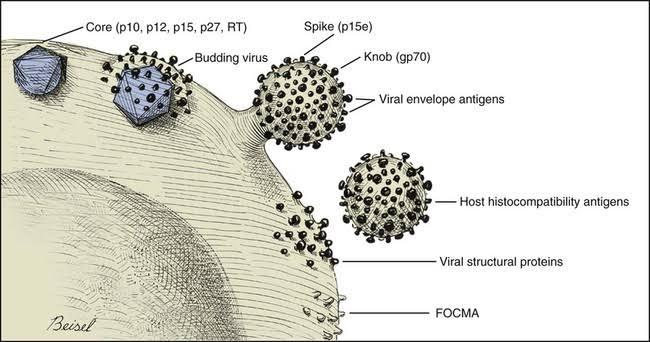

FeLV is a retrovirus belonging to the family Retroviridae, which is specifically harmful to cats. It is a virus that can alter the DNA of infected cells, leading to various forms of malignancy or immune system failure. There are three major subtypes of FeLV (A, B, and C), each of which causes different health complications.

- FeLV-A is the most common subtype and the primary form that is transmitted between animals. It can cause mild disease but often progresses to more severe forms as it spreads.

- FeLV-B is an infected strain that arises when FeLV-A undergoes a mutation. It is often associated with a higher risk of cancer and other complications.

- FeLV-C is the least common and most aggressive subtype, responsible for severe anemia and often leading to death within weeks of infection.

In lions, the virus behaves similarly to how it does in domestic cats, but given the larger size and different environment of wild cats, the disease's manifestation and impact may differ. FeLV can be particularly devastating in wild populations, where the ability to treat or manage the disease is limited.

How FeLV Affects Lions

Lions, like domestic cats, are susceptible to FeLV infection. The virus can be transmitted through direct contact with an infected animal, especially via saliva, nasal secretions, or blood. Since lions often live in prides, the virus can spread quickly within a group, making it a significant concern for conservationists and veterinarians. In the wild, the transmission rate might be lower compared to captive environments, but close contact among pride members still poses a risk.

Once a lion is infected with FeLV, the virus targets and weakens the animal's immune system. In the early stages, infected lions may show no signs of illness, making it difficult to diagnose. However, as the disease progresses, a range of symptoms may develop:

- Immunosuppression: The virus attacks the bone marrow and impairs the immune system, leaving the lion vulnerable to opportunistic infections.

- Cancer: FeLV is strongly linked to lymphoma (a type of cancer) and leukemia in cats, including lions.

- Anemia: As the virus damages red blood cells, affected lions may develop anemia, leading to fatigue, weakness, and pallor.

- Reproductive Issues: Female lions may experience infertility or miscarriage, while males may exhibit reduced sperm quality or loss of libido.

Infected lions may also experience weight loss, poor coat condition, gastrointestinal issues, and a lack of appetite, among other symptoms. The virus is often fatal in lions, particularly if the animal develops secondary infections or cancer. In many cases, infected lions die within months or years of contracting the virus.

Transmission of FeLV in Lions

FeLV spreads primarily through direct contact between infected and uninfected individuals. The main transmission routes include:

- Saliva: Grooming or mutual licking among pride members can easily spread the virus.

- Biting: In the wild, lions are territorial animals and may engage in aggressive interactions, including biting, which can facilitate the virus's spread.

- Urine and Feces: FeLV can also be transmitted through bodily fluids like urine and feces, though this is less common.

- Mother to Offspring: FeLV can be transmitted from an infected female lion to her cubs during pregnancy or through nursing. This vertical transmission poses a significant threat to the lion population.

While transmission is relatively easy, not every lion exposed to the virus will necessarily become infected. Some individuals may be able to mount an immune response and fight off the infection, while others may develop chronic infections that lead to disease progression.

Diagnosis of FeLV in Lions

Early detection of FeLV is crucial in preventing the spread of the virus within a pride. There are several diagnostic tools used by wildlife veterinarians to detect FeLV in lions, including:

- Blood Tests: The most common diagnostic method is the FeLV antigen test, which detects the presence of the virus in the lion's bloodstream. This test can be done in the field or at veterinary clinics. A positive result indicates active infection.

- PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction): PCR testing can detect FeLV genetic material in the blood, which helps to identify whether the virus is replicating in the animal.

- Serology: Blood samples may also be tested for the presence of antibodies to FeLV. A positive serological result indicates previous exposure to the virus, but it does not necessarily confirm an active infection.

- Clinical Signs: In some cases, veterinarians may diagnose FeLV based on clinical signs such as anemia, weight loss, or unexplained infections, although these signs alone are not conclusive.

In wild populations, testing can be challenging, especially since lions are difficult to approach and capture. In such cases, conservationists may use non-invasive methods, such as collecting feces or hair samples, though these methods are not as reliable as direct blood tests.

Treatment and Management

Unfortunately, there is no known cure for FeLV, and treatment is primarily supportive. However, there are several management strategies that can help improve the quality of life for infected lions:

- Antiviral Therapy: Although no cure exists, antiviral medications may be used to reduce the viral load and slow the progression of the disease. These medications can help control symptoms and prolong life.

- Immunotherapy: Researchers are exploring the use of immunotherapies to boost the immune system of infected lions. While promising, these treatments are still experimental.

- Nutritional Support: Proper nutrition is essential for maintaining the health of an infected lion. Providing a high-quality diet can help manage secondary infections and anemia.

- Isolation: In captive settings, infected lions may need to be isolated from other animals to prevent the spread of the virus. This is especially important in zoos or wildlife sanctuaries where multiple species are kept in close proximity.

In the wild, managing FeLV infections is more difficult. Preventing the virus from spreading within a pride is crucial, but without the ability to isolate animals or provide direct medical care, conservation efforts often focus on reducing risk factors, such as controlling lion populations and limiting human-induced stressors.

FeLV in Lion Conservation

FeLV poses a significant threat to lion populations, particularly in Africa, where lions are already facing numerous conservation challenges. The virus can have a negative impact on small or fragmented populations, which are more vulnerable to extinction due to inbreeding and disease outbreaks. Some key conservation strategies to combat FeLV include:

- Surveillance and Monitoring: Conservationists regularly monitor lion populations for signs of FeLV, conducting blood tests and other diagnostic assessments.

- Vaccination: Although FeLV vaccines are available for domestic cats, their use in lions has not been widespread due to logistical and financial challenges. There is ongoing research into developing effective vaccines for wild feline populations.

- Habitat Conservation: Protecting natural habitats and minimizing human-wildlife conflict helps reduce the stress on lion populations, which can lower the risk of disease transmission.

- Captive Breeding Programs: In some cases, infected lions in zoos or wildlife sanctuaries may be part of breeding programs aimed at preserving the species. These programs require careful monitoring to prevent the spread of FeLV to other animals.

The Impact of Feline Leukemia Virus (FeLV) on Lions: A Comprehensive Overview

Feline Leukemia Virus (FeLV) is a retrovirus that has long been recognized as one of the most perilous viral infections affecting domestic cats, and its impact on lions (Panthera leo), both in the wild and in captivity, is an area of growing concern within the field of wildlife medicine and conservation. FeLV is an immune-suppressive disease that weakens the lion’s ability to fight off other infections, thus making it a major health threat to the species. The virus is known to damage the bone marrow, lymphatic tissues, and organs, thereby weakening the animal’s immune system and leaving it susceptible to secondary infections, cancers, and a range of other diseases. Lions, like other felines, are highly social animals that live in prides, and their interactions within these groups increase the likelihood of the virus’s transmission. FeLV is primarily spread through close contact, including the sharing of food, grooming, and through saliva, urine, feces, and blood. The virus can also be passed from mother to offspring, either during pregnancy or through nursing, which makes cubs particularly vulnerable. The virus is highly contagious and can spread rapidly within a pride, creating a situation where multiple animals can become infected. Once a lion becomes infected with FeLV, it can lead to a variety of health problems, including immunosuppression, anemia, reproductive failure, and cancer, with lymphoma being one of the most common and devastating types of cancer associated with the virus. Infected lions may experience chronic weight loss, loss of appetite, lethargy, and fever, and their immune systems become severely compromised, leaving them at high risk of secondary infections like pneumonia or gastrointestinal issues. These infections can sometimes lead to the animal’s premature death. One of the most insidious aspects of FeLV is that lions infected with the virus may not show any immediate signs of illness. In the early stages, an infected lion can appear outwardly healthy, making it difficult to detect and diagnose the virus before it spreads within the pride or affects other lions. As the disease progresses, however, the lion’s health deteriorates, and signs such as swollen lymph nodes, poor coat condition, and respiratory distress may become more apparent. This latent period complicates efforts to contain the virus, especially in wild lion populations, where testing and monitoring can be difficult due to the challenges of capturing and testing wild animals. In captive environments like zoos or wildlife sanctuaries, where lions are often housed in close quarters, the virus can be transmitted more easily. In these settings, lions can be isolated from other animals to prevent the spread of FeLV, but this is not a viable option in the wild, where lions roam over large territories. Once the virus spreads within a pride, the collective health of the group is compromised, and the risk of transmission to other species or even to humans, although rare, becomes a concern. Despite the severity of FeLV, there is currently no cure for the virus, and treatment is largely supportive. Infected lions are often given antiviral drugs and immune-boosting therapies, but these treatments are not a cure and can only extend the life of the lion for a limited time. In some cases, nutritional support is also provided to help the lion maintain strength and resist secondary infections. However, the overall prognosis for FeLV-infected lions is poor, particularly in the wild, where access to veterinary care is limited. The disease’s impact on lion populations is particularly troubling for conservationists working to protect the species in the wild, where lions already face numerous threats, including habitat loss, human-wildlife conflict, poaching, and a declining prey base. FeLV compounds these threats by weakening individual lions and reducing their ability to reproduce, which in turn diminishes the overall genetic diversity of the population. The loss of genetic diversity is a critical issue in conservation biology, as it can lead to inbreeding and the subsequent decline in fitness of the population, further jeopardizing the species’ survival. In addition to the health and reproductive risks posed by FeLV, the virus also affects the social structure of lion prides. Lions are social animals that depend on the strength of their pride for hunting and defense against rival predators. A pride weakened by illness may struggle to find food, protect their territory, or defend themselves against other predators, further increasing the likelihood of death for infected individuals. In some cases, lions with FeLV may become more vulnerable to predation or displacement by other predators, as their weakened state makes them less capable of defending themselves. Despite the challenges posed by FeLV, there are ongoing efforts to monitor and manage the disease in both wild and captive lion populations. Conservationists use a variety of methods to detect and track FeLV in lions, including blood tests, PCR (polymerase chain reaction) testing, and antigen detection, which can identify the presence of the virus before clinical symptoms become apparent. These tests are crucial for monitoring the spread of the virus in both captive populations, such as those in zoos, and in wild populations, particularly in national parks and reserves. However, conducting these tests in the wild presents significant logistical challenges. Lions are difficult to capture, sedate, and sample, and even when samples can be obtained, the cost and complexity of testing in remote locations are major obstacles. In light of these challenges, some conservation programs focus on creating awareness about the virus and encouraging wildlife protection agencies to take proactive measures, such as limiting human-wildlife conflict and reducing the potential for disease transmission between different wildlife species. One of the most promising strategies in managing FeLV in lions is the development of vaccines. While vaccines for domestic cats are available and effective, vaccinating wild lions presents significant obstacles. The logistics of vaccine distribution in remote areas and the cost of implementing widespread vaccination programs in wild populations are two of the primary challenges facing wildlife veterinarians. Despite these challenges, research is ongoing into the development of vaccines specifically designed for wild felines, including lions, that could potentially reduce the incidence of FeLV and other diseases in the future. Habitat conservation also plays a key role in managing FeLV in lion populations. By protecting the natural habitats of lions and reducing human interference, conservationists can help reduce the stress on lion populations, which in turn strengthens their immune systems and reduces the risk of disease. Creating safe corridors for lions to travel and encouraging the growth of prey populations also contribute to the overall health and sustainability of the species. As the global human population continues to expand, the need to balance human development with wildlife conservation becomes increasingly urgent. Protecting lions from diseases like FeLV requires a multifaceted approach that includes habitat preservation, veterinary intervention, and public awareness. In conclusion, while Feline Leukemia Virus represents a significant threat to lions, its impact is not insurmountable. Ongoing research, combined with proactive conservation efforts, offers hope for mitigating the spread of the virus and improving the health and survival of lion populations. FeLV is a stark reminder of the fragility of wildlife populations in the face of emerging diseases, but with continued dedication and innovation, there is still a chance to protect lions and other endangered species from this devastating virus. By focusing on prevention, early detection, and long-term conservation strategies, the fight against FeLV can become an integral part of the larger efforts to preserve and protect the lion, one of the most iconic and important species in the animal kingdom.

The Impact of Feline Leukemia Virus (FeLV) on Lions: An In-Depth Exploration

Feline Leukemia Virus (FeLV) is a retrovirus that has long been recognized as one of the most dangerous viral infections affecting cats, and its presence in lions (Panthera leo) is a significant concern in both captive and wild settings. FeLV targets the immune system, impairing the lion’s ability to defend itself against infections and diseases. The virus, which is primarily transmitted through saliva, urine, feces, and blood, can easily spread within close-knit social structures like lion prides. This increases the risk of widespread infection among lions in the wild, where they live in close proximity to each other, and in captivity, where enclosures often contain multiple animals. Once a lion is infected, the virus begins to damage its bone marrow and lymphatic tissues, leading to immunosuppression, anemia, and an increased risk of developing cancer, particularly lymphoma. Affected lions often experience significant health deterioration, including weight loss, lethargy, and in some cases, organ failure. The virus can also negatively impact reproductive health, with female lions suffering from miscarriages and infertility, while males may experience reduced sperm quality and fertility. Infected lions may initially show no clinical symptoms, making early detection difficult, which in turn complicates efforts to prevent its spread. The diagnosis of FeLV in lions is typically confirmed through blood tests, including FeLV antigen detection or PCR testing, although these tests are not always accessible in remote wildlife areas. As FeLV is incurable, treatment generally focuses on supportive care, including antiviral medications, immunotherapy, and nutrition management, aimed at boosting the animal’s immune system and prolonging its life. However, these treatments are limited in their effectiveness, particularly in wild lion populations where intervention is more challenging. In captivity, infected lions may be isolated to prevent further transmission, but in the wild, preventing the spread of FeLV becomes much more complicated. In fact, due to the large size and aggressive nature of lions, coupled with their social structure, isolating infected animals is often not an option, which makes the disease even harder to control. Conservationists and wildlife experts are particularly concerned about the potential impact of FeLV on lion populations in Africa, where the species is already under threat from habitat loss, human-wildlife conflict, poaching, and declining prey availability. FeLV may exacerbate these challenges by reducing the overall health and reproductive viability of affected prides. Surveillance programs are in place to monitor the spread of the virus among lion populations, but testing in wild lions is logistically difficult, often requiring the capture and sedation of animals, which can be costly and disruptive. Captive breeding programs have been explored as a means to preserve genetic diversity in the face of diseases like FeLV, though these programs face their own set of challenges. Despite the existence of vaccines for domestic cats, their use in wild felines such as lions is limited, mainly due to the practical difficulties of administering vaccines in the wild and the financial constraints of wildlife conservation efforts. Thus, the focus has shifted toward better understanding the virus’s transmission dynamics, developing more effective monitoring techniques, and identifying ways to reduce stressors on lion populations, as chronic stress can weaken the immune system and make lions more susceptible to diseases like FeLV. In some cases, such as in certain zoos or wildlife sanctuaries, FeLV-positive lions may be given antiviral medications and supportive care, though the absence of a cure limits the potential for a full recovery. Moreover, the long-term effects of FeLV on wild lion populations are still not fully understood, and further research is needed to determine how the virus interacts with other factors affecting lion health and survival, such as nutrition, environmental stress, and genetic diversity. Ultimately, FeLV’s presence in lion populations adds a layer of complexity to the already fragile conservation status of lions, requiring continuous efforts in research, disease management, and habitat protection to ensure the long-term survival of these iconic predators. The ongoing battle against FeLV in lions, along with other threats, calls for a multi-faceted approach that includes disease surveillance, captive breeding programs, education, and, most importantly, the preservation of their natural habitats, which will provide the best opportunity for both domestic and wild felines to thrive in a world increasingly affected by human activity.

Summary

Feline Leukemia Virus (FeLV) is a dangerous retrovirus that affects both domestic and wild cats, including lions. Infected lions suffer from weakened immune systems, anemia, cancer, and reproductive issues, and often face a shortened lifespan. FeLV is transmitted primarily through close contact and bodily fluids, which makes it a significant concern in both captive and wild lion populations.

Currently, there is no cure for FeLV, and treatment is primarily supportive, including antiviral medications and immunotherapies. Conservation efforts focus on monitoring lion populations, preventing disease spread, and protecting natural habitats to reduce the risk of FeLV transmission. Research into vaccines and more effective treatments for wild felines is ongoing.

Conclusion

FeLV poses a substantial threat to lion populations, especially those in captivity or isolated areas where transmission risks are higher. While efforts to manage and prevent FeLV in lions are ongoing, it is critical for conservationists and wildlife veterinarians to continue their work to develop better diagnostic tools, treatment options, and preventive strategies. Protecting lions from FeLV is essential for ensuring the survival of this iconic species, particularly in the face of other threats such as habitat loss and poaching.

Q&A Section

Q1: What is Feline Leukemia Virus (FeLV)?

Ans: FeLV is a retrovirus that primarily affects cats, weakening their immune system and leading to severe health problems such as anemia, cancer, and immunosuppression. It can spread through saliva, urine, feces, and blood, and is particularly dangerous to lions due to their social structure, making it easier for the virus to spread within prides.

Q2: How is FeLV transmitted in lions?

Ans: FeLV is transmitted through close contact, especially through saliva (grooming or biting), as well as urine, feces, and blood. In wild lions, transmission can occur when they interact closely within prides or during aggressive encounters. It can also be passed from mother to cubs during pregnancy or through nursing.

Q3: What are the symptoms of FeLV in lions?

Ans: Lions infected with FeLV may show symptoms like weight loss, lethargy, fever, poor coat condition, swollen lymph nodes, and anemia. As the disease progresses, affected lions may develop secondary infections, organ failure, or cancer, particularly lymphoma. Some lions may not show any symptoms in the early stages, making it harder to diagnose.

Q4: Can FeLV be cured in lions?

Ans: Currently, there is no cure for FeLV. Treatment is largely supportive, focusing on antiviral medications, immune-boosting therapies, and proper nutrition to help the lion maintain strength. However, these treatments only help manage the disease and extend the lion's life for a limited time, rather than offering a complete cure.

Q5: How is FeLV diagnosed in lions?

Ans: FeLV is diagnosed through blood tests, including FeLV antigen detection and PCR (polymerase chain reaction) tests. These tests detect the virus's presence in the bloodstream or its genetic material. In wild lions, testing can be difficult due to the challenges of capturing and safely sampling the animals.

Similar Articles

Find more relatable content in similar Articles

Explore Other Categories

© 2024 Copyrights by rPets. All Rights Reserved.